Generating an AH-HaH! moment

|

THE ORCHID PAVILION Wang Xizhi |

|

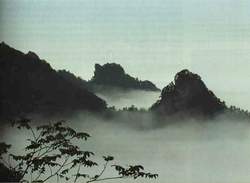

at the beginning of late spring,

we met at the Orchid Pavilion

in Shan-yin of Kweich'i for the Water Festival, to wash away the evil spirits.

Here are gathered all the illustrious persons and assembled are both the old and the young.

Here are lofty mountains and majestic peaks, trees with thick foliage and tall bamboos.

Here are also clear streams and gurgling rapids, catching one's eye from the right and left.

We group ourselves in order,

sitting by the waterside,

and drink in succession from a cup floating down the curving stream;

and although there is no music from string and wood-wind instruments,

yet with alternate singing and drinking,

we are well disposed to thoroughly enjoy a quiet intimate conversation.

Today the sky is clear, the air is fresh and the kind breeze is mild. Truly enjoyable it is to watch the immense universe above and the myriad things below, travelling over the entire landscape with our eyes and allowing our sentiment to roam about at will, thus exhausting the pleasures of the eye and ear.Now when people gather together to surmise life itself,

some sit and talk and unburden their thoughts in the intimacy of a room,

and some,

overcome by a sentiment,

soar forth into a world beyond bodily realities.

Although we select our pleasures according to our inclination

some noisy and rowdy, and others quiet and sedate

yet when we have found that which pleases us,

we are all happy and contented,

to the extent of forgetting that we are growing old.And then, when satiety follows satisfaction,

and with the change of circumstances, change also our whims and desire,

there arises a feeling of poignant regret.In the twinkling of an eye, the objects of our former pleasures have become things of the past, still compelling in us moods of regretful memory.Furthermore, although our lives may be long or short, eventually we all end in nothingness,Great indeed are life and death.

said the ancients.

Ah! what sadness!I often study the joys and regrets of the ancient people, and as I lean over their writings I see that they were moved exactly as ourselves, I am often overcome by a feeling of sadness and compassion and would like to make those things clear to myself. Well I know it is a lie to say that life and death are the same thing, and that longevity and early death make no difference.

Alas! as we of the present look upon those of the past, so will posterity look upon our present selves. There, I have put down a sketch of these contemporaries and their sayings at this feast, and although time and circumstances may change, the way we will evoke our moods of happiness and regret will remain the same.

What will future readers feel

when they cast their eyes upon this writing!

Wang Xizhi

(303-79) [Wang Hsi-chih]

or

Lanting Ji Xu (蘭亭集序)

Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion

Translator's notes:

Incidentally, the manuscript of this essay, or rather its early rubbings, are today the most highly valued examples of Chinese calligraphy, because the writer and author, Wang Xizhi, is the acknowledged Prince of Calligraphy. For three times he failed to improve upon his original handwriting, and so today the script is preserved to us in rubbings, with all the deletions and additions as they stood in the first draft.Note taken from a report of Christie's Auction House in New York in December, 1992.

Ellsworth again defeated all competition to purchase lot 3, a Song rubbing kaishu [standard script] calligraphy by the great 4th century master Wang Xizhi, for US$99,000. Since calligraphy is a classical and conservative art form, it is not surprising that many works relate to either Wang Xizhi or to the most important event in calligraphic history, The Orchid Pavilion.Since 900 B.C. the Chinese had preserved poetry and examples of calligraphy by etching them in stone. Over the years rubbings were made from these stones which constituted a kind of "publishing." Now most of these stones have been lost but examples of the rubbings remain. The above translation by Lin Yutang in Gems from Chinese Literature, in Hong Kong in 1901, was taken from a rubbing.